The government professes that it wants the UK to become a life sciences superpower. But its policies are having the opposite effect.

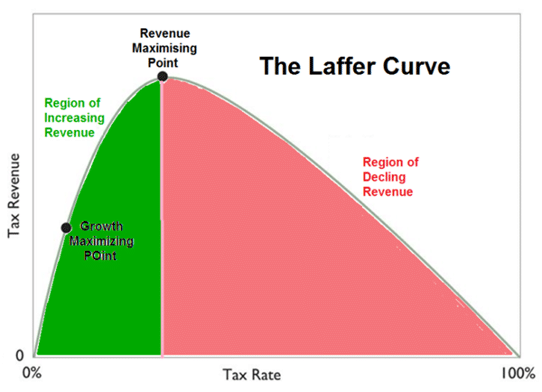

The Laffer Curve was first described by American economist Arthur Laffer in 1974, where he presented the idea to US President Gerald Ford that taking more money from a business in the form of tax leaves it with less money to invest and incentivizes tax avoidance or moving overseas. In addition, workers become disincentivized from working harder, leaving individuals with less cash to spend in the economy.

This idea was instrumental in later President Ronald Reagan’s so-called supply-side and trickle-down Reaganomics, which resulted in one of the biggest tax cuts in history, and was responsible for US tax receipts booming from $344 billion in 1980 to $550 billion in 1988.

Of course, economics are not as simple, and other factors such as infrastructure or an educated population can be just as important as the taxation regime. Laffer Curve critics have existed since the day the man spoke up. But the idea that there is a bell curve, the peak at which increasing taxation rates result in less taxation income is compelling to me.

And last week’s AstraZeneca (LON: AZN) decision is the essence of the Laffer Curve in action.

FTSE 100: AstraZeneca shares

AstraZeneca is hugely important to the UK economy — with a market cap of £178 billion, it’s the largest company on the FTSE 100. It was also jointly responsible for developing the first Covid-19 vaccine and is therefore tremendously symbolic of the country’s economic capability as well as being the flagship for the life sciences sector.

It therefore came as a shock — though shouldn’t have — to the government when this life sciences A-lister announced that it would be building its new £320 million ‘state-of-the-art’ factory in the Republic of Ireland instead of the UK, citing our ‘discouraging’ tax rate. For context, Ireland’s corporation tax rate is set at just at just 15% for larger companies — and this is set to rise from 19% to 25% in the UK in the new tax year.

It appears that Chancellor Hunt, though ‘disappointed’ with the decision, understands the ‘fundamental case they’re making which is that we need our business taxation to be more competitive.’ However, he argues that bringing down taxes would have to be funded by borrowing, despite the high tax rates very clearly being responsible for the now reduced tax take.

And CEO of the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) Dr Richard Torbett argues that ‘there are more stories about losing investment, like the one we’ve seen with AstraZeneca, than the positive noise stories coming in, and we really have to turn that around.’

Life sciences implications

I have covered some of the specific tax disincentives for UK biotechs to grow elsewhere, but AstraZeneca’s decision only further highlights the gulf between the government’s ambition for the country to become a ‘life sciences superpower,’ and the raw reality of the decisions taken by big business on purely economic terms.

One of the other key issues that was factored into AZN’s decision is the pricing agreement codenamed VPAS (voluntary scheme for branded medicines, pricing, and access), which acts as an NHS-branded medicine sales levy. Companies who participate in VPAS, such as AstraZeneca, must refund excess sales revenue over the agreed limit, which increases at only 2% per year.

Not only has the cost of participation soared because of rising demand caused by the pandemic, but the 2% cap pales in comparison to double-digit inflation. The formula was designed in a pre-pandemic, low inflation era, but companies are now paying 26.5% of UK revenues — revenues not profit — to the government before corporation tax is calculated.

In the past, this figure used to remain steady at circa 8%, a fair compromise given the UK’s financial centre and university-led expertise. Torbett argues that the scheme is now ‘vastly in excess of anything the industry pays anywhere else in the world and we have to get to the point where the UK is able to compete for investment on a level playing field.’

Worse, VPAS used to deliver excellent value for pharmaceutical companies. In a symbiotic relationship, our biotechs used to be able to rely on the NHS to help run clinical trials, but underfunding of the service means it is now no longer a reliable partner.

ABPI statistics show that the UK is now the tenth largest host of phase III clinical trials, down from fourth in 2017. Indeed, the organisation claims that on more than one occasion, pharma companies have had to relocate UK clinical trials abroad due to ‘significant delays in costing and contracting negotiations resulting from ongoing issues with the NHS’s research capacity.’

For context, clinical trials often offer life-extending or saving medical care as a high-risk last resort for patients out of options, and close to death’s door. Weakened research capacity and a hostile tax environment is depriving UK citizens of the chance of receiving this care which has been developed in their own country.

It’s all the more galling when you consider that AstraZeneca developed and distributed the world’s first covid-19 vaccine on a profit-free basis — and getting the vaccine in the UK not only saved thousands of lives, but in pure economic terms allowed politicians the political capital to permanently lift lockdowns, generating billions of what would have been lost revenue for UK PLC.

GSK CEO Emma Walmsley seems equally equivocal about internal investment in the UK, warning that the life sciences sector is already at ‘tipping point.’ The former vaccines tsar Dame Kate Bingham has also called out the sector, pointing out in the Financial Times that it is ‘still the object of suspicion and incomprehension within parts of government.’

Of course, despite the ‘B’ word and the country’s exclusion from the EU Horizon research program, AstraZeneca still has its £1 billion Cambridge facility. It remains perhaps the best UK business growth story of the past decade and will continue to spend huge amounts of money in our economy.

But the chasm between government aspirations and the dull toothache of inept policy is widening. And if our very best and brightest biotech company doesn’t find the UK investible, it won’t be long before the next possible star trial, factory, or company sets up shop elsewhere.

This article has been prepared for information purposes only by Charles Archer. It does not constitute advice, and no party accepts any liability for either accuracy or for investing decisions made using the information provided.

Further, it is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person in any country or jurisdiction where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation.