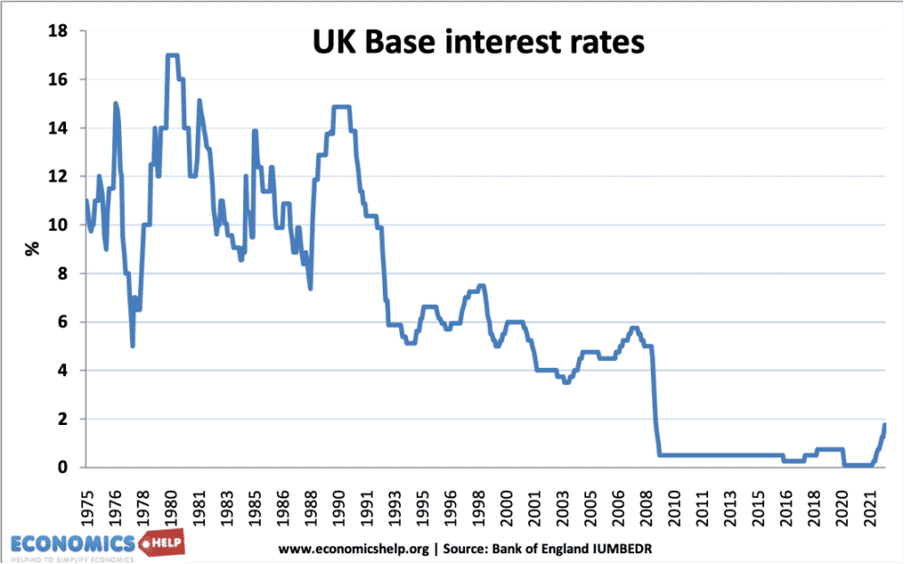

Most analysts expect that the UK base rate will settle below 5%. A rise to double-digits seems unlikely — but another one-off event cannot be ruled out.

In October 2022, I made the case that a 10% base rate was coming for the UK. At the time, the country was reeling from the devastating effects of the Truss-Kwarteng era mini-budget. With the damage now largely under control — with a new unpopular pair in charge — it’s tempting to think that the current market expectations that rates will peak below 5% are realistic.

Of course, there is some hangover from the mini-budget, Questions over LDIs remain, and figures from the Bank of England’s Andrew Bailey to Lloyds of London’s John Neal have warned that the UK has taken a serious hit to its hard-won financial reputation.

But the wider argument from the Bank of England is that its prior predicted two-year-long recession will now be milder and last just over a year. Meanwhile the National Institute of Social and Economic Research thinks the country may avoid a recession altogether — though warns it will not feel like it for millions of lower-paid workers as it predicts households will suffer a £4,000 annual hit to their finances.

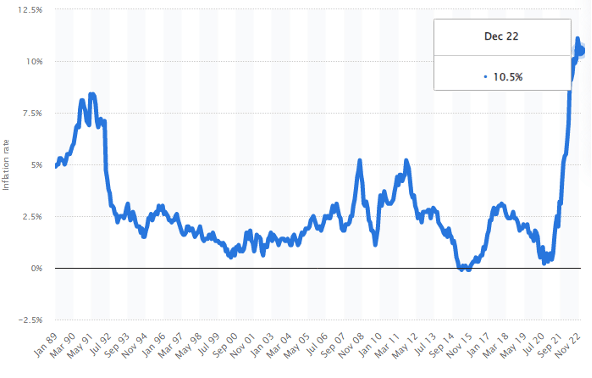

Moreover, the Bank expects that CPI inflation, having fallen from 11.1% in October to 10.5% by December, will fall to 5.2% by Q4 2023 and then dip below the standard 2% target in early 2024.

Of course, even after generating £895 billion of quantitative easing and circa £400 billion for the pandemic response, the Bank considered that inflation would remain ‘transitory’ even as analysts on all sides sounded the warning alarms.

And current stats show that inflation falling back to this level may be wishful thinking. XpertHR analysis shows that employer salary increases are currently at a median of 6% — below headline inflation but still the highest in 30 years.

There’s record growth in private sector earnings, and unlike in the US, France, or Germany, investment in the UK remains below its mid-2016 level according to OECD data. Meanwhile the IMF has warned that the UK will fare worse than any other developed country in 2023, including sanction-hit Russia, mostly because of high energy costs and low government spending.

On top of this, there’s record economic inactivity among the over-50s, a combination of a failing health service, pandemic realignment of priorities, high taxes and pension limits, and the ability of some fortunate enough to retire early.

Indeed, not everybody on the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee is so sure that inflation is on the way down. Its most hawkish member, Catherine Mann, has warned against the prospect of ‘policy boogie’ and recently argued for a larger increase than January’s 50 basis points.

The member pointed to ‘material upside risks’ of inflation sticking at higher levels than expected as the tripartite of Brexit, the pandemic, and the Ukraine War weigh on the country’s economy. In a speech in Hungary, she noted that ‘We need to stay the course, and in my view the next step in Bank rate is still more likely to be another hike than a cut or hold.’

Even with all this data, most analysts expect that inflation has peaked, and that interest rates are also near their peak, with an analyst consensus for a base rate peak of 4.5% by mid-2023. Importantly, most analysts consider that the rates above 5% could spark a housing market collapse with contagion almost certainly infecting the wider UK economy over the near midterm.

However, there is one last factor that is not, and cannot, be factored into standard analysis. And that’s the unexpected.

Consider the past 15 years of UK economic history. Few saw the 2008 credit crunch coming, and eight years later, the vast majority of analysts expected that the UK would vote against Brexit in 2016. The covid-19 pandemic — a so-called once-in-a-generation event — again took the country by surprise and storm in 2020. And then in early 2022, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine was again a surprise, with most analysts arguing that it would *never* happen.

Further back, consider the shock impact on interest rates of Black Wednesday in 1992.

Given the wider global economic problems and geopolitical instability, the risk of another one-off event appears to me to be palpable — the problem is that another economic shock could come from multiple possible sources.

And if — or when — it comes, rates could still rise up to double-digits.

This article has been prepared for information purposes only by Charles Archer. It does not constitute advice, and no party accepts any liability for either accuracy or for investing decisions made using the information provided.

Further, it is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person in any country or jurisdiction where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation.