A placing RNS is the constant fear of AIM investors, while spectacular gains are also never far from their minds.

As a high risk, high reward investor, many of my favourite stocks can be found on the Financial Times Stock Exchange Alternative Investment Market — or FTSE AIM as the snazzy acronym goes. I also like to go hunting for AQSE shares on occasion, though this market is unregulated, and many investors steer clear, regardless of promise.

I thought it would be worth breaking down how the AIM market works.

FTSE AIM

AIM began life in 1995 with just 10 companies generating a combined market capitalization of circa £82 million. Since then, it’s helped nearly 4,000 businesses raise over £100 billion — and now lists 711 constituents with a net market capitalization of around £55 billion.

To visualize this number more easily — that’s about three Tesco’s or one Glencore.

The London Stock Exchange maintains three AIM indexes: the FTSE AIM 50, the FTSE AIM 100, and the FTSE AIM ALL-Share. Unsurprisingly, companies tend to do better if they move into one of the higher echelons, as they then qualify for institutional investment, passive investment inclusion, or even simply larger retail interest.

For context, many retail investors invest in AIM shares for the tax benefits including complex inheritance tax rules; and this class of investor will not touch companies that are not in the top 100 list. Similarly, institutions looking for sustainable growth may not invest in anything outside of the top 50.

This creates a self-fulfilling prophecy, as qualification for the higher bracket immediately sees greater investor interest — and more importantly, a wealthier class of investor.

The types of companies looking to list on AIM are usually smaller, privately held ventures which cannot gain access to private capital on favourable terms — but can raise cash quickly through an IPO. This makes most fairly high risk initially, as if they were lower risk, they could get access to private financing.

Key considerations

Nomads — or Nominated Advisers, are key to regulation on the AIM market, acting to advise AIM company boards pre and post-IPO. When you read an RNS, the Nomad is meant to work through it with a fine toothcomb to check for accuracy and compliance issues.

However they also usually profit from fees, or payment in shares, from the company they are advising, which puts their impartiality in question. Often, this leads to ambiguous RNS releases, where the Nomad attempts to hide negative detail — contributing to the generic RNS issues I’ve gone into in depth before.

Regulation — on a related note, AIM is seen as a far more speculative market due to relaxed, or ‘light touch,’ regulation compared to the likes of the FTSE 250 and FTSE 100. Again this is mostly because companies are expected to self-regulate by use of a Nomad, with investors accepting this additional risk. There are two sides to this coin. High risk investors can make extraordinary amounts of money in early stage companies — Novacyt’s 6,890% return in 2020 remains a prime example, and my opinion is that several junior resource companies will see similar growth in 2024.

However, there have been many cases of outright fraud on the market, with a common complaint being that investors close to company boards are given privileged insider information before the wider market is informed. This is true to the point that investors sometimes call certain companies ‘leaky,’ as their share prices react to news before it is officially announced.

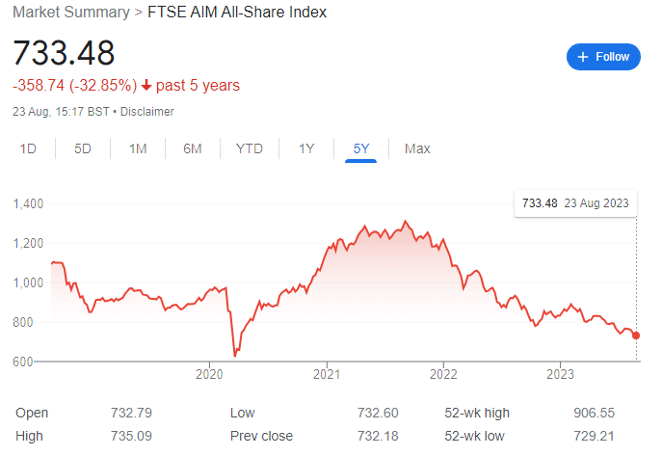

Cyclical Risk Premiums — as AIM shares are higher risk, they tend to become more popular in times of loose monetary policy. The market has been falling since September 2021 — just before the Bank of England started hiking the base rate.

This is no accident. Investors now have the choice to park their money in bank accounts paying out risk-free rates of circa 6%, with defensive dividend stocks, bonds, and gold also all doing better as rates rise and quantitative tightening turns the screws.

Reallocation of cash away from risk assets is inevitable, though the correction is now arguably overdone. Since the 1990s, there are clear cycles of rises and falls, and I suspect we are now close to the bottom.

Inverse Blue Chips — one of the most popular investing strategies for a FTSE 100 dividend investor is to buy a cheap index tracker that invests in all 100 of the UK’s largest companies by market cap, and then profit from the near guaranteed dividend income.

This is a popular strategy for a reason. It’s easy to do, very cheap, and is only slightly riskier than a typical savings account over the longer term, but with better returns.

But FTSE AIM investing is the inverse. If you invest in a premium segment index tracker — and it doesn’t matter whether it’s the S&P 500, NASDAQ 100, Dow Jones, FTSE 100, CAC 40, ASX 200, et al — then your money will almost certainly grow over the longer term.

If you do this on AIM, you will probably lose money. The index itself is down circa 33% over the past five years, and even in bull cycles, investing in the AIM index delivers a smaller return than investing in the larger indices.

This means that success is based on picking winners in an ocean of losers — and accepting you will occasionally get it wrong. A huge part of this is lack of research — picking AIM shares involves massively more research than a blue chip share, as dozens of analysts will have already done most of the legwork for you.

On a related note, there will also be huge volatility on the way to profits, so a willingness to ‘buy and hold’ is critical.

Placings — The FTSE 100 offers dividends and share buybacks, while FTSE AIM offers capital gains and share placements. A ‘placing’ is the stuff of nightmares for many AIM investors, as they are usually priced at a discount to the current share price. Indeed, the share price usually drops to the placing price in the immediate aftermath.

Worse, more shares in issue dilutes your own shareholding, and makes a stock more volatile. But placings are absolutely essential for most AIM shares on the growth to profitability, so just like a business investor needs to inject more capital to continue the growth story, it’s important to look at the justification for a placing — and crucially, how many placings might be needed.

Paying bloated management salaries is not the same as paying for a new drill programme, for example. Similarly, raising cash to pay for short term issues is fine — but issuing shares to keep a zombie company alive is not. There’s a subjective element to judging this, but one of the key things is that investors know a placing is coming.

If they know, it suggests that there is a wider plan. If it comes out of the blue, then usually one of two things are happening; either the company is being mismanaged, or it’s cleverly taking advantage of a temporarily improved share price to the long term benefit of investors.

If the cash raised is well used, then it can be a good thing over time. The company’s cash balance is immediately boosted, and typically, new investors come on board who were waiting for the placing to occur. Frustratingly, if it’s common market knowledge that a placing is coming, then investors sell to buy the manufactured dip, creating a bigger dip and necessitating a larger placing.

On the other hand, popular companies can churn new shares fast. And investors sitting on the sidelines risk a company raising cash in a more immediately positive way — for example, through an institutional lender, or else a strategic partner buys shares at a premium.

The bottom line The FTSE AIM market is a high risk, high reward arena littered with poor companies, but with some of the best opportunities you can find anywhere.

The general idea is to find the diamonds in the rough, invest, and profit. But it’s harder than it sounds.

This article has been prepared for information purposes only by Charles Archer. It does not constitute advice, and no party accepts any liability for either accuracy or for investing decisions made using the information provided.

Further, it is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person in any country or jurisdiction where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation.