OPEC has played this particular gambit before. It didn’t work then, and it won’t work now.

Brent Crude — the North Sea oil benchmark — traded for an average of circa $70 per barrel in 2021, $42 in 2020 (when oil went negative for the first time ever), and $64 in 2019.

BP CEO Bernard Looney infamously advised that the oil major constituted a ‘cash machine’ even at November 2021 prices. Record profits at BP, Shell, Exxon et al duly followed, with Saudi Aramco posting a $161 billion profit in 2022, the largest annual profit ever recorded by an oil and gas company.

Unsurprisingly, oil companies the world over would like the bonanza to continue. But in using cartel power, they are telling the markets that demand is falling. And in oil, high prices have ever been the cure for high prices.

Oil price: history rhyming

Let’s rewind to the 1979 — hardly ancient history and a perhaps an excellent lesson for oil investors.

In early 1979, the Iranian Revolution ended with the fall of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, generating significant turmoil and reduction of oil exports. 2023 may be seeing a different revolution in Iran— but this time the other way round.

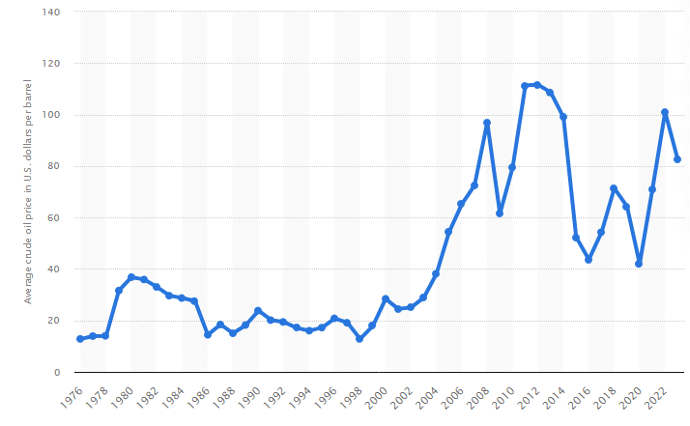

As the global supply of oil slumped, shortages and panic buying followed, seeing the price of oil double within a year to $39.50 — $120 inflation-adjusted. There was even rationing across major US states, including days where consumers could not purchase gas.

Indeed, there were even fears that there would not be enough heating oil to last the winter. Sound familiar?

Of course, US policy was also to blame, as the government regulated oil prices, had windfall taxes in place, and had ordered refiners to restrict gas supplies thus increasing prices. These policies were swiftly ejected as the crisis started.

The Federal Reserve, which was already facing high inflation, didn’t want to increase interest rates too quickly fearing recession, leading to high inflation for longer.

Why was inflation so high? A variety of factors; overspending on the Vietnam War, the 1973 OPEC oil crisis whereby the cartel imposed an embargo on the US for its support of Israel in the Yom-Kippur War, the classic wage-price spiral, expansionary monetary policy including lowering interest rates and printing excessive fiat, and weaker comparable productivity.

Again, sound familiar?

Volcker was brought in in 1979 — where the federal funds rate had averaged 11.3% — and raised it to a peak of 20% in June 1981. This led to the 1980-82 recession and a 10% unemployment rate, and was accompanied by huge political attacks for the much-needed tonic.

Faced with a similar decision last month, Powell capitulated. Eventually he will need to be replaced with Volcker 2.0.

But this second crisis in a decade prompted utility companies to seek out oil alternatives and spend billions on R&D on other fuel sources — including nuclear, coal, natural gas and ethanol blended gasoline. In 2023, the new drive is for wind, solar, and renewables — and also another drive for energy independence.

These efforts saw worldwide oil consumption decline between 1979 and 1985, with OPEC’s global market share falling from 50% to 29%.

This ‘oil glut’ — or global surplus of crude — saw oil fall to an inflation-adjusted average of just $26.80 in 1986, with the then CEO of Exxon noting that in the US and Europe, oil consumption had fallen by 13% between 1979 to 1981, ‘in part, in reaction to the very large increases in oil prices by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries and other oil exporters.’

Or in layman’s terms the cure for high prices, was high prices. Commercial exploration exploded in Siberia, Alaska, the North Sea, and the Gulf of Mexico, while non-OPEC producers doubled their output in the six-year period.

Specifically, the Alaskan Prudhoe Bay Oil Field entered peak production, supplying 2 million bpd of crude oil in 1988, at the time 25% of all US oil production. Note that current US President Jo Biden has just approved the $8 billion Willow oil project in Alaska.

Between 1980 and 1986, OPEC decreased oil production several times, overall nearly by half. However, its control of the global market crashed nonetheless. In September 1985, Saudi Arabia publicly raged that other OPEC countries were either inflating their reserves to achieve higher quotas, refusing to stick to them, or just lying outright about production.

Thereafter, the world’s largest oil producer went full production, and oil fell to as low as $7 per barrel.

The prisoner’s dilemma only ends one way when you can’t trust the others.

So after already promising cuts last year, when Russia says it will again cut production by 500,000 bpd in the midst of an expensive war and surging Chinese demand, does Saudi Arabia really believe them? How long will they stick to their own equivalent cut?

The Soviet Union, weakened by its 1979 invasion of Afghanistan, which ended with withdrawal ten years later, saw the oil glut contribute to its collapse. In 2023, Russia is being weakened by Ukraine and is once again wholly dependent on selling oil. If oil collapses again, Russia’s toast.

Currently, Goldman Sachs predicts that these new cuts will send oil back above $100 per barrel from its current $80 price. Speaking at a conference in Saudi Arabia, analyst Jeff Curie warned that ‘by May, oil markets should flip to a deficit of supply compared to demand…that could use up much of the unused capacity global producers have, which will be positive for prices.’

But if oil becomes more expensive, inflation rises, and then so do interest rates. Then there’s a global recession and demand destruction anyway.

Of course, the key difference is China. Demand from that quarter could help keep prices up.

But the cartel members did not trust each other in the 1980s, and they don’t trust each other now.

They can’t fight supply and demand.

And if you think they can, pick up a history book. Fighting market forces never ends well.

This article has been prepared for information purposes only by Charles Archer. It does not constitute advice, and no party accepts any liability for either accuracy or for investing decisions made using the information provided.

Further, it is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person in any country or jurisdiction where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation.