It’s possible to think that corporate ESG – environmental, social and governance – investing is a thoroughly good idea. Which is how fashionable society seems to see it right now. It’s also possible to think that corporate ESG is merely a passing fad and an expression of the agency problem – precisely because fashionable society currently likes it.

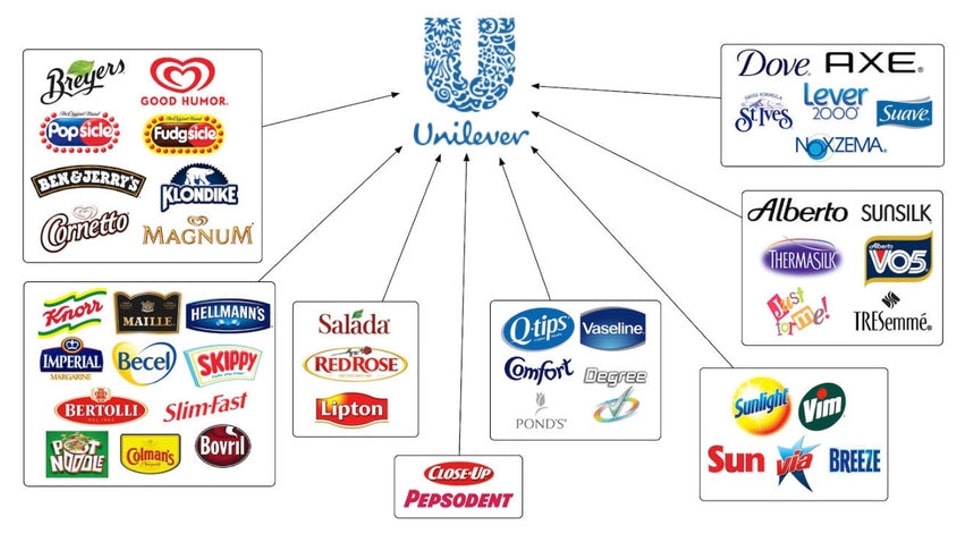

Unilever (NYSE: UL) (LON: ULVR) (AMS: UNA) has been at the forefront of this movement. As the former CEO puts it: “Companies that position themselves toward being more sustainable and inclusive are more likely to attract investors, particularly from Gen Z and millennial age groups, according to former Unilever CEO Paul Polman.“ Or as Terry Smith, one of the City’s better fund managers, has put it: “a company which feels it has to define the purpose of Hellmann’s mayonnaise has in our view clearly lost the plot. “

There is value in that initial thought. Not boiling the planet seems to have some value, not dealing with slavers in your cobalt supply, these sorts of things. But the value is really in not that the business is pure, but that investors see it as pure and therefore value it more highly. We’ve taken issue here before with ESG investing. If everyone does value it more highly then the returns from investing in the ESG saints will be lower – that’s what other people valuing something more highly means.

Putting ESG into reverse

But the argument now is the other way around. What if ESG investing doesn’t raise the value of the equity of the company being all saintly and ESG?

As an explanation of this we need to look at Agency Theory. This is the idea that other people have their own ideas and agendas. This is true even when we hire them to do something for us. When we’re hiring management of a company it’s called agency theory or the principal-agent problem – when we’re hiring government and bureaucrats it’s called public choice theory. The base idea is that they do what is good for, interests, them. What we get is only what’s left over, or perhaps enough for those folk to keep their jobs and keep gaining their own benefits. This is obviously true at some level and how much it’s the driving force of everything depends upon how cynical we are.

What does Unilever gain from ESG and woke?

At which point what corporate management gains from being ESG. Well, they get to go to all the right parties, the more air-headed among potential sexual partners admire them and so on. Investors may get nothing at all – because other investors might not value ESG in quite the same way that correct-thinking fashionables do. So, ESG could be something that benefits the management and not investors. Could be note, not is, just could be. This being rather the thing we’re trying to work out.

The evidence we’re getting from the new CEO of Unilever is that perhaps this is fashionable only among the fashionable idea is correct. “Unilever’s new chief executive said that the idea of corporate purpose could be an “unwelcome distraction” for some brands.“ Or, as it’s also possible to put that, sure we’ll be woke when we’re trying to attract the woke consumers – Ben and Jerry’s say – and more ruthlessly capitalist when we’re not. “Unilever to tone down social purpose after ‘virtue-signalling’ backlash Dove and Hellmann’s maker says it will no longer seek to ‘force-fit’ brands with a cause.” Or even, that this is no longer true: “Our sustainability materiality process helps us report on the issues that matter most to our business and stakeholders.“ Or an even better translation – we’re only going to do this woke stuff when it actually is of interest to anyone and not when it’s only what gets the management team invited to the right cocktail parties.

So what difference does ESG make for investors?

What we want to know is what difference this is going to make to share prices of course. As above, if ESG really works – it makes investors value an income stream more highly because it is pure – then we want to be investing in the not-ESG yet people. Because the earnings stream will be cheaper. So, pile into ‘baccy and oil. If it doesn’t work – as seems likely – then we still want to avoid the ESG crowd. Because they’re doing expensive things that don’t raise valuations. But if it does work then we want to be in the about to become ESG stocks, because they’re about to rise in value. And if it doesn’t then we want to be in the soon to be ex-ESG because their earnings will increase as they forgo the extra expenses.

Which is, really, rather annoying. In that even if ESG does not work – or does – it will still change relative share prices. We’ve got to make up our mind on which way we want to go even if it’s that exercise in futility.