Inflation, Sino-Western tensions, falling ore quality and excess plant capacity are all creating a flourishing mergers and acquisitions environment.

As an investor in multiple LSE-listed mining small caps, and an analyst of the larger titans, I have a fairly wide view of the mining industry.

And the key thing I keep coming back to is that there is going to be huge consolidation of the industry over the next five years – specifically where a small cap has a quality deposit of a critical mineral. Think copper, graphite, lithium or REEs.

I’ve covered many of these companies in depth both here and elsewhere — but the list is seemingly endless. PREM, MARU, BRES, FCM, MKA, TGR, GROC, KOD, ALL…these companies all have one thing in common. They hold the rights to excellent deposits, but need further investment to realise the potential — some more than others.

On the other side of the coin, the mining titans are looking for acquisitions and mergers. Newmont and Newcrest, BHP and Oz, Albemarle and Liontown — these will just be the start.

Here’s why.

Four mining consolidation factors

1. Inflation, recession, and supply chains

One of the key factors to consider when analysing a definitive feasibility study – and this goes for any project – is all-in sustaining costs. Essentially, this is the costs associated with getting a mineral out of the ground, processing and selling it.

After a DFS, it typically takes months or even years to start production, so there are dozens of operations coming online that are only profitable – or profitable enough – in a low inflation environment, high growth environment with strong supply chains.

Of course, inflation remains substantially above 2% in most of the developed world, growth has been dramatically shut down, and supply chains have been decimated by the twin attacks of the pandemic and the Ukraine War.

This means that where previously companies might have jealously guarded their reserves, it now makes sense to consolidate to bring down costs and share supply chains.

2. China vs the West

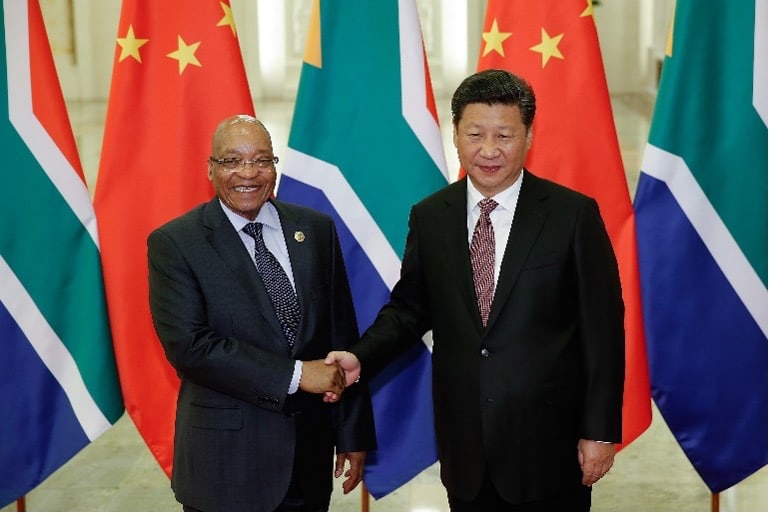

In every critical mineral space – whether lithium, copper, graphite, or otherwise -China has spent decades slowly buying up shares in junior explorers, promising to fund initial studies and pilot plants in return for exclusive access to any offtake, before then conducting full buyouts.

This has been happening predominantly in African copper belt nations, the South American Lithium Triangle, and the Pilbara region of Australia – the areas where I focus much of my personal research. Accordingly, China not only has a stranglehold of critical minerals, but also of processing facilities.

The West appears to be waking up to this new battlefront, finally, issuing critical minerals strategy documents, which I believe will soon lead to tax breaks on exploration as the situation becomes more desperate.

Crucially, where there are small caps with quality deposits, there will likely be bidding wars between western and Chinese companies, with both incentivised by state inducements.

3. Falling ore quality

A common story of the titanic miners – think Glencore, BHP, Rio Tinto etc – is that historical legacy reserves of critical minerals are either drying up or producing lower ore grades. This is pushing up costs when costs are already elevated, while reducing sales volumes and prices simultaneously.

In Australia, the partnership between Greatland Gold and Newcrest is a solid example -Greatland found the world-class Haverion gold deposit, and brought on Newcrest as partner, because its nearby Telfer mine now has excess processing capacity as the original mine starts to run dry.

But this story is being told across the world – in Chile’s copper mines, in Australia’s copper deposits, and Turkey’s graphite pits. As ore quality falls, larger miners are being forced to pay a premium for quality new deposits from the small caps.

This trend be explained in one of two ways.

Either this is an error of their own making, having paid out excess dividends rather than focusing on sufficient exploration.

Or it’s a smart strategy to allow many smaller companies to do the heavy lifting of finding the deposits – with many failing in the process – and then buying out the successes for a premium smaller than the total cost of exploration.

4. Excess plant capacity

I just touched on this, but excess plant capacity is a growing phenomenon that isn’t just because ore grades or quantity is falling. It’s a feature of small cap mining.

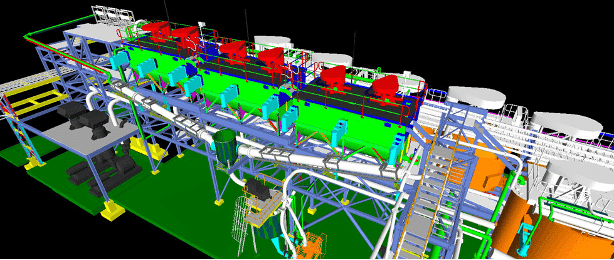

There are broadly speaking two routes to go down when considering how to start mining a new deposit – either a quick-start dense media separation plant which takes circa a year to get online, or a flotation plant which is objectively superior, but takes longer to build and costs far more.

But both plants often end with excess processing capacity. A DMS can usually benefit from modular expansion – so one company can expand their DMS to process a fellow company’s ore while they build a flotation plant.

Alternatively, a flotation plant can have far more capacity than is needed at one project, so the attached company will offer to process ore at nearby projects for a fee. This incentivises both large and small miners to look at merger deals to further optimise profitability.

Final comments

There is a global recession coming at the same time as long-term critical mineral supply gaps widen due to increased demand from green tech and clean energy needs. Together these macro factors are generating a healthy mergers and acquisitions environment, as small cap explorers and large cap producers both look for ways to cut costs and up production.

And where a small cap has a quality deposit, current mineral prices are relatively irrelevant. Security of supply is the dominant factor dictating negotiations – and this will only be accentuated through the 2020s.

This article has been prepared for information purposes only by Charles Archer. It does not constitute advice, and no party accepts any liability for either accuracy or for investing decisions made using the information provided.

Further, it is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person in any country or jurisdiction where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation.