The mechanics, the politics, McCarthy, and why it really is different this time.

Every so often, the prospect of a US default rears its ugly head. The common wisdom is that the government will always push through some kind of ‘fudge,’ an unhappy middle ground that keeps the can kicking down the road.

And usually, politicians opposing an increase to the US ‘debt ceiling’ are using the fear of default as leverage in negotiations elsewhere — but this time might be different.

But let’s get the basics right first.

What is the US debt ceiling?

There are five key points to grasp regarding the debt ceiling. It’s a lot more complicated than this in reality, but as an overview:

- The debt ceiling is a limit set by the US Congress on the amount of money the federal government can borrow to finance its operations. Only one other country (Denmark) has a debt ceiling.

- When the government spends more money than it collects in revenue (i.e. from taxes), it borrows the difference by issuing securities like Treasury Bonds. The debt ceiling, therefore, determines the maximum amount of debt the government can issue.

- If the debt ceiling is reached, the US Treasury Department must balance the books to ensure that only completely essential government activities continue without issuing additional debt. For example, it would reallocate funds from various government accounts to maintain system critical departments.

- Failure to raise the debt ceiling would have serious consequences. It could lead to a government shutdown, in which non-essential government services are temporarily halted, and would also result in the government defaulting on its existing debt obligations.

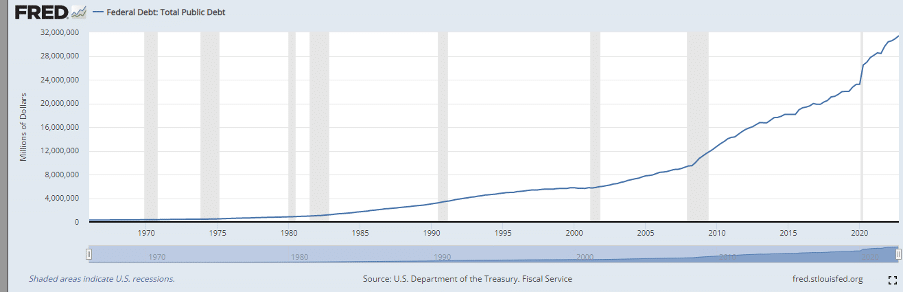

- In the past, Congress has raised the debt ceiling whenever necessary to avoid default and ensure the government’s ability to meet its financial obligations. However, the debt ceiling has become a truly contentious issue. National budgets are not the same as household budgets, and economists disagree on whether continually spending more than brought in by tax will lead to disaster.

Goldman Sachs analysts believe that 10% of the country’s GDP would collapse overnight if a default occurred, including the loss of 1 million governmental roles, and millions more jobs in the private sector. The scarring effect would also be extremely damaging, especially as defaulting on governmental debt could cause a crisis of confidence in the banking industry and spark another financial crisis.

Of course, the US has come so close to default so many times that many investors find it hard to care.

However:

This time it’s different

It’s worth noting that if there actually were a default, the government could technically choose to raise taxes to cover the additional spending — though this would go against the low-tax principles of the Republican Party. Instead raising the debt ceiling is the precedent, having been done three times during Trump’s Presidency.

The problem is that Speaker Kevin McCarthy faced significant problems when securing the votes required to become Speaker back in January — and he eventually had to promise the GOP that he would not request an increase in the debt ceiling until he presented a budget that would achieve balance over the next ten years.

To be fair to the hardliners, US debt is increasing out of control. This is not sustainable, and past promises that the debt problem would be addressed after the latest ‘emergency’ has been resolved have not been kept.

Further, in order to prove his mettle to the house, he changed House of Representatives rules so that it takes just one member to call a vote for him to be ousted as leader of the chamber, which gives greater power to the hardliners.

Republicans hold a slim 222-213 majority.

The problem is that achieving a ‘balanced’ budget is not possible. This isn’t a political point, and it doesn’t matter who’s in charge. The shortfall between taxes and spending is so large that Congress could eliminate the entire funding of the US defence department, and the budget still wouldn’t be balanced — by a margin of hundreds of billions of dollars.

This puts McCarthy between a rock and a hard place. He’s already promised not to raise taxes or make cuts to Medicare or Social Security, which are two of the biggest areas of government spending. Given Ukraine and Taiwan, it’s politically impossible to argue for cuts to defence.

Therefore, to balance the US budget, everything else would have to go. Education, transportation, energy, science, housing, border control; the list is endless and completely impractical.

Now of course, those politicians on the right of the Republican party — roughly 30 staunch holdouts — don’t honestly believe that McCarthy will be able to propose a completely balanced budget; much less that it would ever or should ever get through. But they want some substantial cuts. And they are in a powerful position to force compromises — because it would take just five of these 30 members to vote against McCarthy to unseat him.

The Speaker’s issue is that even if he approves a deal which doesn’t require those 30 Republicans to back him, they can then act to eject him from his position.

And while politicians are not usually in a habit of putting the greater good before their own careers, the hardliners do have a point.

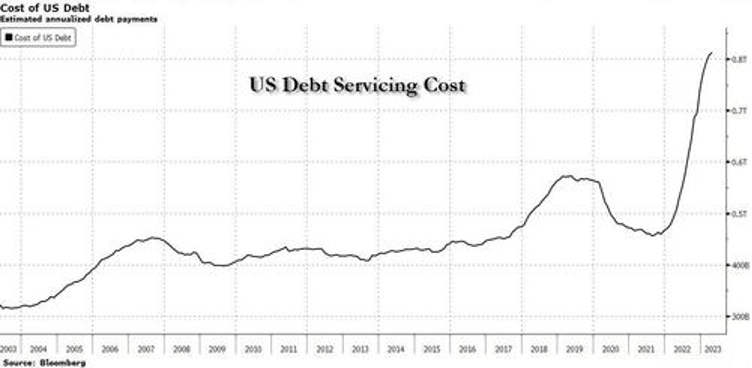

Total US debt servicing costs are now higher than the US defence budget. It’s more than the capital expenditure, salaries, and equipment cost of fielding the entire US armed forces. Calls to scrap the debt ceiling ignore the long-term problem — it might stop a crisis now but will simply store up a larger catastrophe for tomorrow.

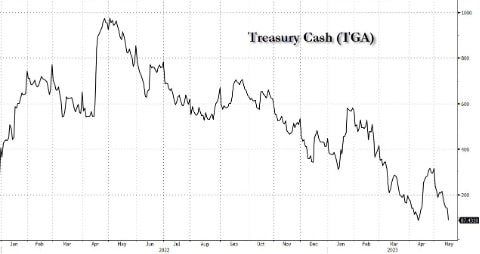

This isn’t a party political point — I’m certain that were party roles reversed, whoever might be the Democrat Speaker would act in the same way. But the Treasury Department has made clear that it could run of funds as soon as 1 June 2023. And this could be sooner.

Treasury cash fell by $52 billion yesterday to just $87 billion.

Just one short-lived proposal, which advocated for cutting veterans’ healthcare, some educational extras, and elements of law enforcement, barely made it through the House of Representatives, but died in the Senate.

There is one archaic workaround which has been used on occasion over the past few decades, which would require at least five Republicans to vote with all the Democrats. Given the seriousness of the issue, this is not completely unthinkable.

Essentially, while the Speaker holds the authority to decide which bills are brought to a vote or not, he can be overridden by a discharge petition — where the majority can force a vote. As the Republican majority is so slim, only five would need to cross the chamber.

These five would be publicly ostracized, but it’s also possible that waverers will be given an unofficial blessing by McCarthy so that he can keep the right wing happy, keep his job, and also not see the country engage in economic collapse.

Just last night, McCarthy came out of a meeting with Biden enthusing that ‘it is possible to get a deal by the end of the week,’ hinting that the Democratic leader is entertaining compromises.

The question is: will it be enough?

Tied into this negotiation is the recent collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and the other regionals — combined with the pandemic hangover and other global crises, a default could not come at a worse time. It could spark Global Financial Crisis 2: return of the credit crunch.

Of course, while this means that right-wing Republicans have more leverage than ever, the Democrats could also call their bluff.

And in this game of high-stakes poker, both parties are all-in.

This article has been prepared for information purposes only by Charles Archer. It does not constitute advice, and no party accepts any liability for either accuracy or for investing decisions made using the information provided.

Further, it is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person in any country or jurisdiction where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation.