With CPI inflation stubbornly high, Governor Andrew Bailey must choose the path of least damage. A recession is imminent.

The Bank of England has two official objectives in its monetary policy remit:

- To keep to a target CPI inflation rate of 2%

- To balance this key target with short-term needs for economic growth and jobs

It has two key tools to perform its duties — setting the base rate and controlling the money supply. While it usually takes a couple for years for interest rate changes to feed into the real economy, it’s usually not too difficult to keep to the 2% inflation target.

Put simply:

When there’s high growth and low inflation, the bank does nothing — this is optimal.

- When there’s high growth and high inflation, the bank raises rates.

- When there’s low growth and low inflation, the bank reduces rates.

Most of the time, a reasonably intelligent nine-year-old could operate the levers of monetary power.

But when there’s low growth and high inflation, the Bank of England has a problem. Increasing rates reduces inflation but can send the UK economy into recession, while reducing rates can grow the economy but send inflation sky-high.

This means that its key economic tool works more like chemotherapy than surgical precision; and because it takes years for the full effects of rate changes to be felt, it’s incredibly difficult to know how to operate.

It’s worth noting a couple of points at this juncture:

- the central bank has created £895 billion of new money in the form of bonds since the 2008 GFC.

- it also kept the base rate at an ‘emergency’ sub-1% for over a decade, even when there was the room for small increases.

The problem is that there was always going to be a risk event eventually. If not a pandemic, then a war. If not a war, then a banking crisis. Of course, the UK was weakened by Brexit in 2016, then hit by the pandemic between 2020 and early 2022 where the government locked down an import-dependent island economy for two years, and then knocked down again by secondary effects of the Ukraine War.

After this, we had the pleasure of the Johnson meltdown, the Truss lettuce debacle, and even came perilously close to another financial crisis in the wake of the Silicon Valley Bank/Credit Suisse collapses in March 2023.

On that note, while some market bullishness has returned, it’s worth mentioning that there was a solid six months between the collapse of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers — the global economy is not yet completely out of the woods.

With demand soaring as the pandemic started to subside, the Bank of England was the first central bank to start raising rates, from 0.1% to 0.25% in December 2021. At the time analysts were thinking a terminal rate of 1% would be sufficient. Fast-forward to this time last year, and the markets were pricing in an increase to circa 3%.

With the bank rate now at 4.5% and widely expected to rise to between 4.75 and 5.00% tomorrow, markets are pricing in an increase to a terminal rate of 6%. This is just 1% below the 7% terminal rate I have considered has been inevitable over the past year. Simultaneously, the Bank is engaging in quantitative tightening, such that not only is money more expensive, but there is also less of it around going forward.

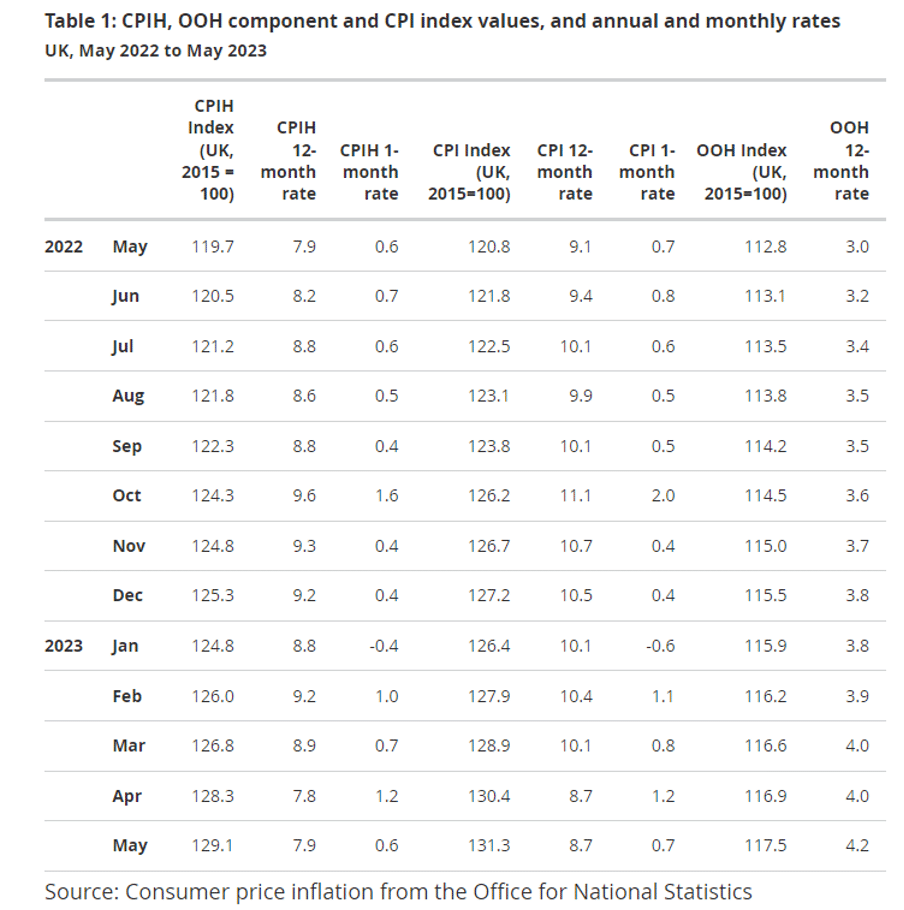

But the problem is that even with the base rate going to 6%, it may not be enough. For context, CPI inflation came in at 8.7% in May, above the 8.4% market consensus. This is unchanged from the last reading, where the consensus was also for a far less hot reading.

It’s notable that purely mathematically, there a problem getting inflation down from where we are now. CPI was 9.1% in May 2022 and rose by only 2 percentage points to a peak of 11.1% by October 2022 — for context, the rise between March 2022 to April 2022 was from 7.0% to 9.0% in a single month, and CPI still came in hot in the same month-to-month movement a year later.

Worse still, in the most recent figures, core inflation — which strips out volatile items — rose to 7.1%, ahead of market expectations that it would stay at 6.8%. This is the highest core inflation since March 1992 — and services inflation also rose from 6.9% to 7.4% in one of the world’s most services-dependent economies.

And let’s be clear, this is becoming a UK-specific problem. CPI across the Eurozone fell from 7.0% to 6.1% in May. In France, the crucial measure fell from 6.9% to 6.0%, and in Germany from 7.6% to 6.3%. Stateside, CPI fell from 4.9% to just 4.0% in April — leaving Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell free to instigate a ‘hawkish pause’ on rate rises, as prices are rising less than half as quickly as in the UK.

But the Bank of England is to some extent limited in what it can do by the side effects of its crude monetary tool — as evidenced by the clear divide between Monetary Policy Committee members including Silvana Tenreyro and Catherine Mann.

There are three main constrictions:

Government costs

Government borrowing costs are already spiking. The yield on two-year gilts (the return promised by the Treasury to investors who buy government bonds) reached a high of 5.09% today, with JP Morgan’s Karen Ward, an adviser to Chancellor Jeremy Hunt and former Bank of England rate setter, warning that the Bank will need to induce a recession to get inflation down.

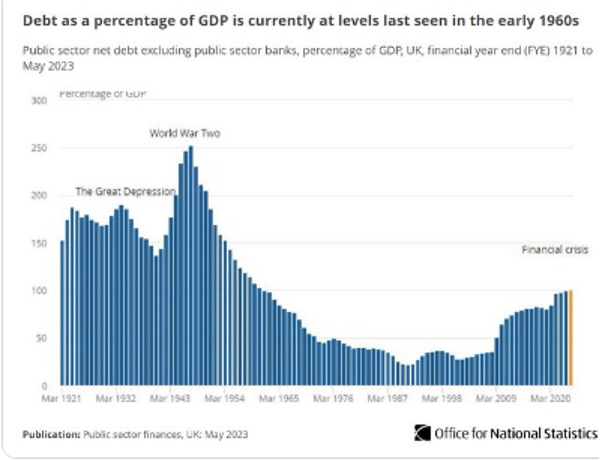

Indeed, UK government debt has now risen above 100% of GDP for the first time since March 1961 — for context, a time before the birth control pill was legalised. Public sector debt excluding public sector banks was £2.567.2 billion at the end of May 2023, provisionally estimated at 100.1% of GDP.

Spending exceeded revenue by £20 billion in May, more than either the OBR or independent analysts had forecasted. Politically, this is a nightmare as it leaves little to no scope for tax cuts, even with the highest tax burden since World War II. Arguably, it’s ended the Conservative reputation for sound finances.

The accountants among us might even want to consider that the 100% figure doesn’t account for the £6.7 trillion of public sector and state pension debt.

Mortgage costs

I’ve talked about the likely house price crash elsewhere, but two key developments from today are interesting to note. The first is that Chancellor Jeremy Hunt has categorically ruled out direct support, noting that ‘we won’t do anything that means that high inflation stays around for longer because that is the root cause of the pressure.’

This confirms my earlier suspicions — but the second factor is just as interesting. Bank official and former Chair of Nationwide, David Roberts, told a House of Lords committee that ‘some of the press headlines are a little bit over where my own judgment would be about what I think could happen – or quite a lot over…(given) the vast majority of borrowers have been stress tested at 6% or 7%, certainly 5%.’

Of course, these stress tests only ever considered the impact of mortgage costs rising, and not the economic environment — such as record food inflation — that would see rate rises necessary.

The influence on house prices given elevated earnings-to-mortgage ratios has been covered to death — mortgages are costing hundreds more for those elevating historical fixed rates behind — but the key point is that the Bank is also signalling that it will keep raising rates.

Employment dangers

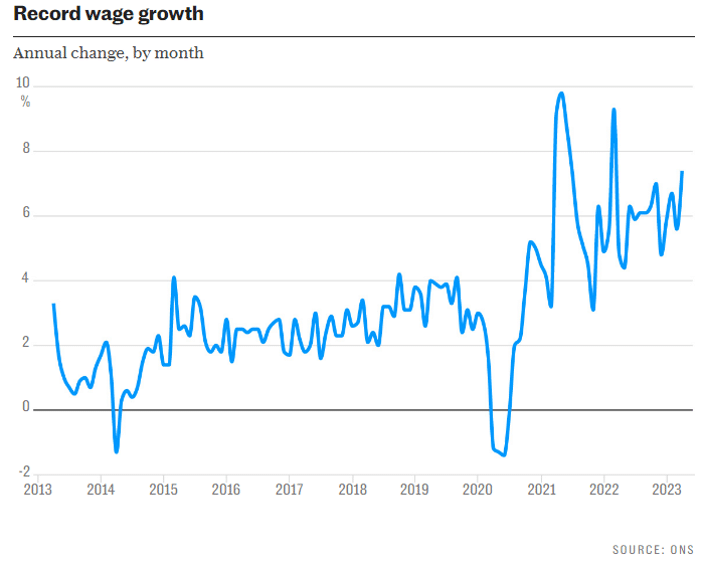

Normally, the UK’s extremely tight jobs market and low unemployment rate would be a boon — but currently, it’s forcing employers to reduce their growth strategies or increase wages on offer to get staff, fuelling the inflation monster.

Ward has warned that ‘a price-wage spiral is emerging’ which the Bank must ‘nip in the bud.’ She warns that it simply has to induce a recession, to create ‘uncertainty and frailty’ in the corporate world. Further, she intoned that the Bank had been ‘too hesitant’ about raising rates thus far.

The problem is that supply chain damage caused by Brexit and the pandemic has already stalled growth to some extent, while an ailing health service with record numbers of sick workers has combined with a general public which refuses to tolerate further wage freezes after a decade of public and private austerity.

The bottom line

Paradoxically, the quickest way to get government borrowing costs down is to increase rates to a point where the Bank brings on a recession. The government knows this, which is why it is refusing to reduce the impact of rate rises on mortgages.

A near-term recession takes the heat out of the jobs market, cools inflation, and creates a scenario whereby the Bank can consider reducing the base rate to perhaps 3.50%-4.00%. The alternative is to let inflation continue to rip, even if it is primarily supply-side and exacerbated by corporate greed.

The only other tool is government fiscal policy, which can be used to increase taxes. But the tax burden is already at its highest in modern history. And there’s yet to be a time where the Central Bank has got core inflation under control without setting the base rate above it.

A terminal rate of 7%, followed by a recession and then a reduction of the base rate shortly after seems the only viable route.

This article has been prepared for information purposes only by Charles Archer. It does not constitute advice, and no party accepts any liability for either accuracy or for investing decisions made using the information provided.

Further, it is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person in any country or jurisdiction where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation.