What is inflation?

At a most basic level, inflation is the rise in prices over time. It also represents the change in purchasing power. As inflation rises, the purchasing power to buy a basket of goods will decline. One unit of currency will be able to buy fewer goods or services than it did previously. In effect, your money does not go as far as it did before.

The concept of a “basket of goods and services” is used to calculate inflation. It is a selection of items and activities that are used to represent the prices for the whole economy. How the prices in that basket change over time is used to calculate the level of inflation.

Inflation is expressed as a percentage change from month to month (MoM) or from year to year (YoY).

Different measures of inflation

Inflation can be measured in a variety of ways. The CPI is broadly viewed as being the most popular and widely followed measure. However, there are other inflation measures to be aware of. Here are some of the important ones:

- CPI (Consumer Prices Index) – The CPI is a measure of change in consumer prices of a basket of goods and services that is representative of the whole economy. It is widely followed by central bankers, economists and markets as being the primary measure of inflation.

- PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditure) – The PCE is a measure of consumer spending in the US that is used by the Federal Reserve as its favoured measure of inflation. The PCE accounts for around two-thirds of domestic spending in the US.

- HICP (Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices) – The HICP measures consumer price inflation across the countries of the Eurozone. The harmonised part means that consumer spending is weighted according to the aggregate levels of countries in the euro area.

- PPI (Producer Prices Index) – Also known as “factory gate inflation” the PPI measures inflation as experienced through the input prices (of raw materials) or output prices (wholesale goods prices) of manufacturers and businesses.

Headline and core inflation

Often when inflation is measured, it comes with various items stripped out:

- Headline inflation – is the raw inflation rate that covers all aspects of price moves.

- Core inflation – is an adjusted measure that strips out volatile categories such as food and energy costs.

Both versions are seen as valid measures of inflation, but often central banks will focus on core inflation for monetary policy decisions.

Inflation, Disinflation and Deflation

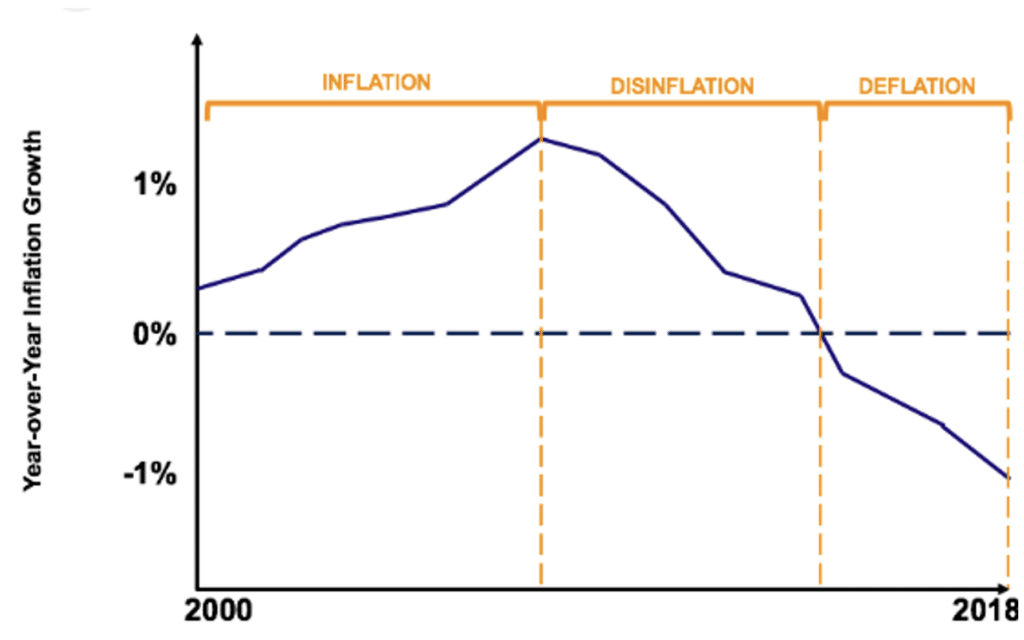

Inflation is the general increase in the level of prices in a basket of goods and services. However, when inflation begins to fall, there can mean disinflation and perhaps even deflation:

- Disinflation – this is where the level of inflation (or price rises) is falling. Inflation is still positive, but inflation is reducing. The rate of increase in prices is falling. A period of high inflation tends to be followed by disinflation as inflation slows down.

- Deflation – this is a period of negative inflation. Deflation is the general decline in the prices in a basket of goods and services. Deflation is considered to be as much of an economic evil as high levels of inflation. If people believe that prices will be lower tomorrow, they will not spend money today. Sustained deflation can push an economy into a downward spiral of stagnation and can be extremely difficult to recover from.

Monetary policy and inflation

Inflation is generally considered by central banks to be the most important issue facing an economy (although the Federal Reserve places it alongside employment in importance).

Subsequently, central banks have inflation targets that they look to achieve. These targets will often be around 2%.

So if inflation sustainably deviates away from the central bank’s target, it will elicit a change of monetary policy to attempt to bring inflation back towards the target.

Changing interest rates alters the cost of borrowing and the amount of interest received from savings accounts in the bank.

Here are the typical policy responses:

- Inflation rising above target – this will drive the central bank to raise interest rates. A higher interest rate makes borrowing more expensive (reducing inflationary pressures). It also increases interest rates for savings accounts, taking money out of the economy and also reducing inflation.

- Inflation falling below target – the central bank will reduce interest rates. This reduces the cost of borrowing in the hope of encouraging economic activity. It also reduces the interest on savings accounts hopefully encouraging savers to spend money instead of getting minimal interest in the bank.

Market reaction to inflation data

Here is how financial markets can be expected to react to changes in inflation. All things remaining equal, higher-than-expected inflation should mean:

- Domestic bond yields move higher – the prospect of higher interest rates would likely drive up bond yields

- Positive for the domestic currency – potentially higher interest rates would encourage traders to buy the currency

- Negative for domestic equities – the potential for higher interest rates makes it more expensive for corporates to borrow but also reduces domestic spending potential.

We can expect markets to move in the opposite way for lower-than-expected inflation.